Note: This essay has been updated for grammar and clarity. A quote was also removed. The original was published on Medium.

I Nearly Missed the Love of my Life

A great romantic story includes a series of obstacles that the two lovers must overcome. A few of mine were fear, anxiety, and familial acceptance. I almost lost my interest in mathematics before our love affair could begin. The intervention of my fourth-grade teacher set me on a path to overcoming my math anxieties. With her help, I was able to meet eye to eye with mathematics and hammer out our misunderstandings.

Elementary school was a confusing time for me. My parents did not pay much attention to what I read or watched. I adsorbed entertainment without them providing much context. There was a benefit to this. I developed my imagination without limitation or censorship. I was able to think things through for myself which inspired my creativity. I journaled, wrote, and painted. I would sometimes cause trouble when left to my own devices.

My creativity caused an incident at my local school. I had arrived dressed in my best Punky Brewster outfit. Wearing mismatched and colorful clothing. My principal saw this and immediately sent me home to change. She was fearful the other children would ridicule my appearance. My parents, outraged by her actions, enrolled me in the local private school.

Like my mother and her sisters, I often used books to escape from my problems. I had long drawn-out arguments with authors. Addressing them by name and writing my disagreements in the margins of my books.

By fourth grade, I had the vocabulary of a teenager and the math skills of a kid in Kindergarten:

-

I couldn’t count change or read the time on an analog clock.

-

I couldn’t tell you which sign stood for “greater than” or “lesser than.”

-

And multiplication wasn’t happening.

SO I FLUNKED 4TH GRADE MATH.

My teacher gave me an F.

Patience and Love Heals Old Wounds

I felt helpless. Something had gone wrong with my mathematical ability. I could see that other children weren’t having the same difficulty. That insight was frustrating.

My family considered the failings of my early years as a rite of passage. They saw their own struggles with math repeated in my experiences. They too felt a form of helplessness when confronted with my problems. They were never quite sure how they could help me. It was easier for them to tell me stories than to sit with me at the table and explain multiplication.

My father tells me the story of his college algebra professor. It was near the end of the semester and the professor lets him know that he would receive a failing grade in his class. This is bad news for my father. If he didn’t have a high enough GPA then he would face expulsion from his fraternity. The professor tells him that he will give him a “D” if he doesn’t try to take calculus next semester. This was because he considered my father such a terrible student that he didn’t want him in another class.

My mother was an award-winning poet and a journalist in high school. She didn’t see math as an important skill for a writer to master. Her teachers did not tell her of her poor abilities. Instead, she felt her inadequacy in the form of her grades. She pursued anthropology as a college major. This was because the major didn’t have much mathematics work.

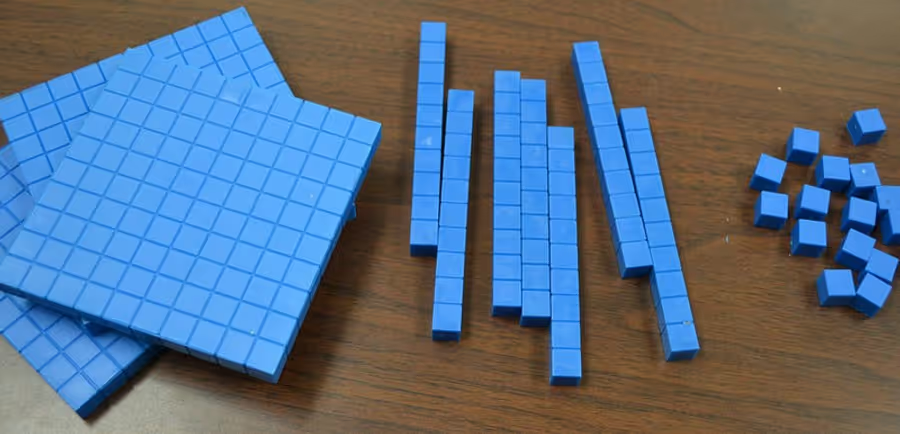

Other people in my life did try to help. I spent many recesses with my math teacher. I remember her bringing out a set of bright orange cubes. There were singles that represented ones. Sticks of cubes represented tens. And slabs made of ten sticks representing hundreds.

“Okay Susan,” she says as she takes a handful of ones and sorts them “I have a group of ten cubes.”

I Nod.

She continues “If I have ten groups of ten cubes, how many do I have?”

This statement launches a chain reaction. I glare at the teacher. Stare blankly at the cubes. Scrunch my eyes in thought. And start counting “one, two, three, four…”

A Love of Words Leads to A Love of Math

In a last-ditch effort, I started wondering how I could lean on my strengths to overcome my weaknesses. I didn’t know what else to do. The authority figures in my life had already reached their limits in on how much aid they could give. I was going to have to make that last cognitive leap on my own.

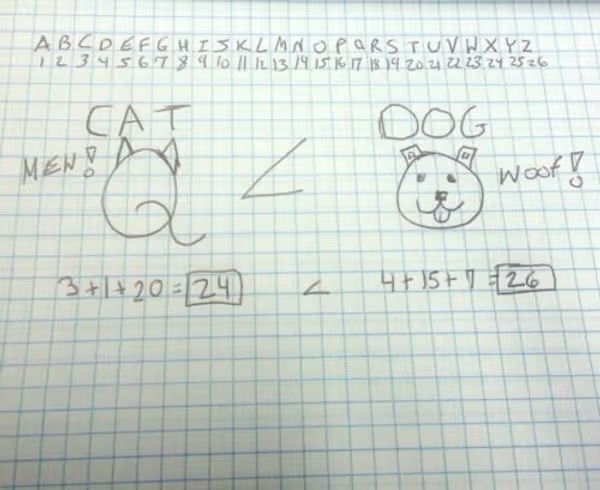

I turned to language and the use of analogy. I remembered my mother’s cryptogram puzzles. Scrambled letters represent everyday sayings using a simple substitution code. The solver must use logic, rules of grammar, and knowledge of common phrases to find the answer. I thought this could also apply to numbers. If a letter could represent another letter then a letter could also represent a number.

I quickly scribbled down this code.

A=1, B=2, C=3, D=4, E=5, F=6, G=7, H=8

Then I transformed my homework problems.

1 x 2 become A x B.

And then suddenly — I saw it for the first time.

That tiny “x” was staring me in the face.

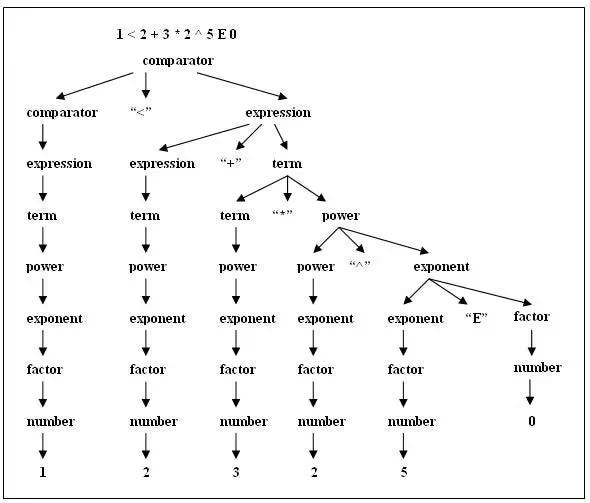

An equation is like a sentence. A mathematical operator is a form of grammar. You have to understand its symbolic meaning. I hadn’t yet conceptualized what that tiny little “x” was trying to tell me. I was counting cubes because I could only see the numbers.

I didn’t know how to read the sentence.

credit: Edwin Law Hui Hean

Love Puts into Perspective What Matters

I had this discussion with a friend who is a math tutor. We were discussing students who come in with math phobia. So I asked, when do you think they start to like math?

My friend answered, “When they become good at it.”

It cannot be a mere skill that determines if we like something or not. My earlier experiences taught me that it takes something more. My skills in mathematics grew as a progression over three or four years. I was able to focus because I had found something more in mathematics than anxiety and fear. I discovered that putting forth cognitive effort could be a pleasurable experience.

I developed my own puzzles as I was learning about my new love. I used my code keys to add up the values of words. I compared their values. I discovered recreational mathematics.

I leaned increasingly more on my math skills over the years. It was like repairing an atrophied muscle. I exercised my number sense through entertaining activities.

I have deep emotional attachments to historical mathematicians, numbers, functions, and certain theorems. Just as you may have attachments to novels or films. These feelings make up my fundamental sense of self. While others perceive my writing skills they may not know much of my inner world of mathematics. Yet both are important to understanding who I am as a person.

I believe people like math when it becomes personally meaningful to them.

Pixar’s “Inside Out” explains the concept of personal meaning with clever visuals. This helps the audience understand the complexity of their own emotions. I applaud the studio for enlisting experts in their research.

When we witness the story of the human protagonist, 11-year-old Riley, it rings true. Her emotions at Headquarters; Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Fear, and Anger really are in charge.

Inside of me, there is a writer with a mathematical muse. The source of my inspiration is the depth of my feelings formed as a child learning to become math literate. These emotions have taught me an important lesson.

We have to face the things which make us feel the most uncomfortable. They also have the potential to bring us our greatest loves.